|

THE COMPLETE

CARNIVORE DIET GUIDE

Learn how to lose weight, fix your gut and cure autoimmune symptoms with our free Carnivore Diet guide.

|

|

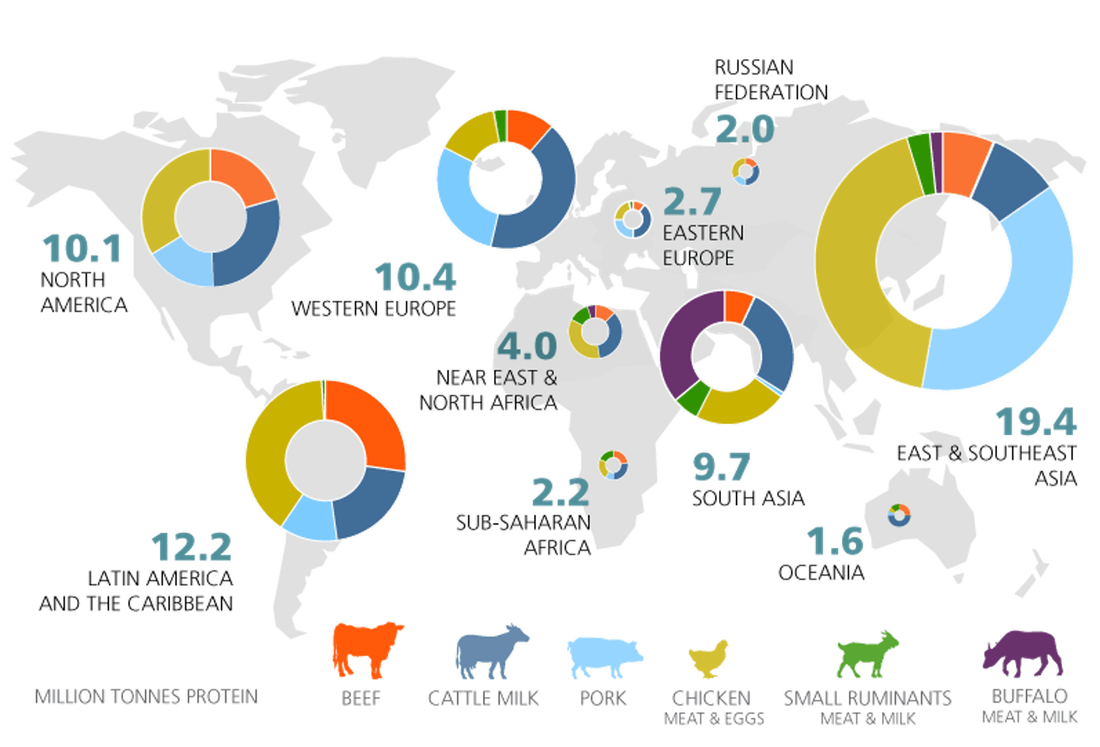

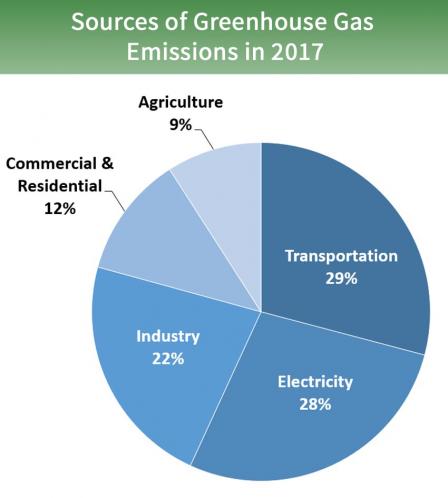

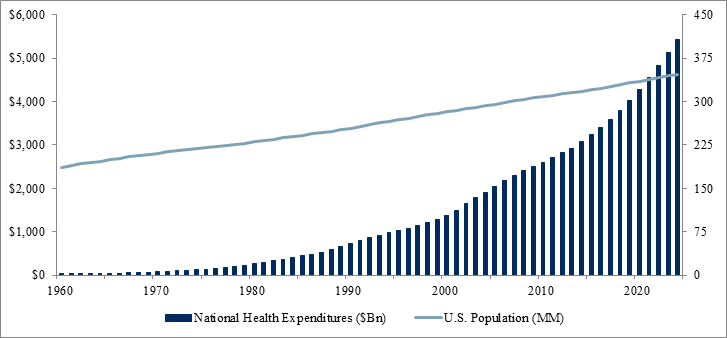

There’s a widespread perception that if people living in Western countries reduced their consumption of meat, then they could save the planet. Meat is seen as a significant emitter of carbon dioxide, and so the theory here is that cutting it from the diet will help reduce carbon footprint. However, the view that meat production is responsible for such a huge carbon footprint stems from a report by the Woolwich Institute published in 2009 that stated that meat production was responsible for 51 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, much more than any other category. In reality, all of agriculture accounted for a total of 9 percent. The total emissions contributed by animal agriculture was less than half of this amount, representing 3.9 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. That’s very different from claiming livestock represents as much or more than transportation. Then, in 2006, the United Nationals Food and Agriculture Organization put out its own study entitled Livestock’s Long Shadow. While it didn’t suggest that livestock were responsible for a whopping 51 percent of global greenhouse emissions, as the Woolwich Instituted later claimed, it still put the figure at around 18 percent - more than all transportation combined (as measured in the report). Just as with the Woolwich Institute study, it led people to a sweeping conclusion: that the best way to cut down on CO2 and save the planet was to stop eating meat. Confused much? Setting the Record Straight So what’s wrong with this picture? The main issue has to do with the methodology of the studies. The original aim of the FAO study was to calculate the total greenhouse emissions embodied in the production of each pound of meat. The authors didn't just measure cow farts. Instead, they included things like CO2 used to transport grain to production facilities, the loss of forest to make way for grazing, and the energy required to grow the feed. Fair, enough, you might say: that sounds reasonable. After all, what we care about is the total energy that goes into meat production, not just the direct emissions of a farm. But the problem is that this is not how the FAO measured the emissions for other big GHG polluters. When researchers looked at the emissions produced by motor vehicles, they only considered the direct GHG emissions from engine exhausts. They didn't include things like the CO2 that was used to make the factories or the roads on which cars drive. It was like comparing apples to oranges. The FAO’s estimate of greenhouse gas emissions from meat production, therefore, was vastly distorted compared to other categories. By taking the life cycle approach, looking at all of the CO2 that goes into meat production to deliver it to your plate, it overstated the total pollution, relative to other categories. It was misleading. Another more reliable report from the US Environmental Protection Agency found that transportation is actually responsible for 28 percent of GHG emissions, electricity generation for another 28 percent, and industry, 22 percent. Giving Up Meat Won't Save The Planet The study’s lead author Henning Steinfeld later retracted the claim that animal agriculture was responsible for 18 percent of all CO2 emissions. The actual figure for agriculture, when measured in the same way as the other categories, was around 9 percent of the global total. Animal agriculture is responsible for about half that - approximately 3.9 percent of total global emissions. Researchers at the University of California took these data and calculated what would happen if every person in America cut meat out of their diet entirely. Their conclusion? It would reduce carbon emissions by around 2.6 percent - something, but not much. Cutting out meat once per week for Meatless Mondays might cut carbon emissions by 0.5 percent. Now, when you also factor in the cost of healthcare from following the current dietary guidelines, and the emmisions produced by the healthcare industry who know what the numbers would look like. And to cap this section off, meat production is becoming greener over time. Data from the FAO’s database suggest that there’s been an 11.3 percent decline in GHG emissions from livestock production over the last sixty years. In that time, the total production of meat has more than doubled. A Solution Worth Exploring Removing meat from the diet could have a small impact on total greenhouse gas emissions, but too little by itself to significantly reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions or prevent man-made climate change.

What’s more, it might make it more difficult for people to obtain nutritional requirements. Advocates of plant agriculture like to point out that you can get fifty times as many calories from a patch of land covered in wheat as you can from the same ground grazed by cattle. While that might be true, it’s also misleading. People need more than just calories to survive: they need foods that contain a full complement of essential nutrients too. Meat is a nutrient-dense food. It offers a substantial quantity of vitamins and minerals per calorie, especially when compared to other sources of energy in the American diet. What’s more, while plants can provide a lot of calories, many of their constituent parts aren’t edible or desirable - for instance, the husk on the outside of the wheat berry. Then there’s the issue of how agriculture can use the land available to it. The idea in the above argument is that all land is perfectly suitable for plant agriculture. Some think that a piece of land is just as adept at raising cattle as it is growing soybeans. However, that’s not the case. According to the FAO's own figures, something on the order of 70 percent of the landmass available to farmers is only suitable as rangeland. You couldn’t grow crops on it, even if you wanted to. Land also needs ruminants, like cattle, sheep, and goats, to maintain it. Without them, it's in trouble. Ruminants have the unique ability to break down cellulose in plants, depositing it on the ground in their dung. The digested material then provides the nutrition grazing land needs to remain viable long term. Climate change requires drastic action, but the evidence presented here suggests that switching to a vegetarian diet won’t help. Worse still, it could lead to nutritional deficiencies if adopted on a mass scale. Furthermore, if everybody went vegetarian, it might lead to the degradation of pasture and grazing land worldwide, with damaging knock-on effects on the global ecosystem. We need to find more efficient ways to make food as the world’s population reaches 9 billion by 2050, but cutting out meat isn’t one of them.

5 Comments

9/21/2020 08:06:23 pm

Thank you! I thought the cow fart thing was overblown.

Reply

Jasmine

5/15/2022 03:44:33 am

Did you know that a large portion of soybean production is used for farm animal feed? So the problem is not only with the land use (and methane as you also mentioned), but also the amount of resources (feed, water, etc) needed to produce that meat.

Reply

Joanne

7/27/2023 06:21:06 pm

But if you look at the breakdown above, changing our purchasing habits and the ways we produce electricity are way more impactful. Taking a position that veganism will save the planet does nothing more than allow people to feel better about their consumerist lifestyles and corporations to deflect blame for their own emissions.

Reply

Gavin

1/30/2024 10:30:30 am

morgen

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Carnivore Diet Recipes & Meal PlansOur Trusted Partners

Popular Guides

|